I love to ask questions. I always have. I remember very distinctly being at an intersection with my mom and insisting that she answer a question. This was before my parents separated so I was really young. I remember my mother shouting, “Not at the intersection!”

I may remember this only because it entered the family lore, though I remember the intersection and the car. But memory works in crazy ways, so I don’t know for sure. Anyway, I soon was the kid who asked questions and demanded that they be answered at the most inopportune moments. I was described this way to myself and to others. My mom still loves to tell me, “When you were little you insisted that I answer questions at intersections.” (I have long since asked myself what’s specifically bad about intersections. I think I could attempt to summarize the main claims of The Critique of Pure Reason for someone in the middle of a six-way, crowded intersection; but hey, that’s me).

Then and now, I’m not sure I know exactly why I love to ask questions. It is certainly the case that there isn’t a single reason and I think I know at least some of the reasons. I know why I ask questions in some contexts. When I am in social situations, for instance, asking questions allows me to shape interactions in a way that suits me and typically pleases my interlocutors too, so, my reasoning goes, everyone wins.

Today I had a little insight into why I so love asking a certain kind of question in therapy. Again, there is most certainly not a single (or simple) reason, and the issue of when and how to answer these questions is one my analyst and I have discussed a lot and keep discussing. I love, though, that she is incredibly flexible about these things. I would hate working with an analyst who takes the not answering of questions as an immutable law of the universe.

In therapy, there is a specific kind of question I really, really love to ask and have answered. Those are questions that concern my analyst’s work and the discipline in general, specifically how she sees it and understands it and practices it. I get tremendous pleasure from these conversations. It is not a kind of excited pleasure. It’s a soothing, fulfilling, filling pleasure that leaves me satiated and calm.

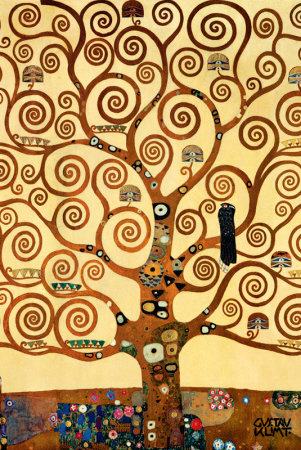

The insight I had today is that this pleasure has to do with being taught. See, I have trouble being taught. When I was little I was insatiably curious and probably very precocious too. I had a million questions in my head. They sprouted like mushrooms and demanded to be answered because so much depended on the answer. Here is an example. I would be reading a book (I read books all the time) and encounter a word I didn’t know. Not wanting to bother anyone, and also wanting to be autonomous, I would pick up the dictionary and look the word up. But the definition always contained words I didn’t know! I would look those up. Their definitions also had words I didn’t know. I would look those up. Ad infinitum.

It was very frustrating to me. I simply couldn’t understand why the people who wrote dictionaries didn’t write them in such a way that you understood your definitions the first time around.

The endless delay of the moment in which I would nail the answer to my problem (in this case, what does the word in my book mean?) was a curse that followed me everywhere. I would ask my mom, “What are people made of?” My mom might say, “People are made of cells.” “What are cells?” “Cells are little bits of biological stuff.” “What do you mean? What are they made of?” “I don’t know exactly.” “Where can we find out?” “In a biology book.” “Do we have a biology book at home?” “No.” “So how are we going to find out?” “We can ask someone who knows.” “Who do we know who knows this?” “Your uncle will know.” “Can we ask him?” “You can ask him next time you see him.” “But I need to know now; can you call him when we get home?” “No.” “Why not?” “Because I can’t.” “But how am I going to find out what cells are?”

This would be about when my mom would start screaming.

This is the kid I was. The answer to my questions always eluded me. Getting answers became more and more urgent to me. I would go crazy hunting down answers. I would go crazy going from one incomprehensible dictionary definition to another. I needed so many answers yet so few were forthcoming.

My mom was not the best mentor or teacher in the world. She was impatient, she had a whole lot on her plate, and, quite honestly, I don’t think she was exactly consumed with the desire to satisfy my need for knowledge. She probably figured it was something I’d get satisfied later in life, like everyone else, by getting a formal education. I am pretty sure that for her my desire to know and understand things was mostly a source of great annoyance, and probably more. She might have found it angst producing. She might have been resentful of me for it. I am suggesting this because I remember becoming really stubborn and insistent, screaming, stamping my feet, getting frantic. I would not have gotten this disorganized if I had perceived calm and self-possession in my mom.

There have been maybe two people who have been really good to me, answer-wise. They have known things and been willing to take me from link to link till I got my answer. But there haven’t been many. Two is not a lot. Formal education has created more questions than it has given answers. I feel I lack so many pieces of the puzzle. Now, I realize we all do, that it is the very nature of knowledge. But I feel the empty spaces in the puzzle very keenly. They torture me. I want to know so, so badly.

In therapy, when I get to ask my therapist about her work and she explains everything to me like we have all the time in the world, the torture of the missing pieces is soothed as if someone lay some fantastic balm on a bad burn injury. My therapist answers thoughtfully and deliberately; she answers with great complexity and sense of nuance; she answers like she owns the material; she answers with incredible competence and assurance. I cannot even express how tremendously gratifying this is for me. It more than makes up for all that screaming between my mom and me when I was little. I am almost happy my mom led me to frustration over and over, because without this terrible frustration I wouldn’t be able to experience such pleasure, solace, and joy now. It’s that good.